We are like butterflies who flutter for a day and think it’s forever.

-Carl Sagan. Cosmos

In my last post I discussed how it was possible to make tentative estimates about the total amount of time that a planet spends in the habitable zone, also known as its habitable period, and why this is important. In this post, I’d like to put numbers to those estimates.

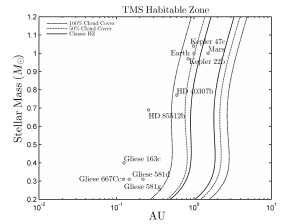

This figure plots the results as a function of star mass, running along the horizontal axis. The vertical axis is in units of billions of years, and is on a logarithmic scale. The dashed line running through the middle (‘mean habitable period’) represents the habitable period that would be expected if a planet was located right in the centre of the habitable zone at the beginning of the star’s lifetime. I’ve included it to highlight the fact that lower mass stars have longer habitable periods. I’ve also included the Earth and Mars, as well as the four habitable exoplanet candidates mentioned in the preceding post.

This simple model, the results of which are outlined in the image above, estimates the Earth’s total habitable period to be approximately 4.91 billion years, meaning that it will end about 370 million years from now. That sounds like a long time, and in the context of human time-scales, it certainly is. Even geologically, the world of 370 million years ago was a very different place. It was the height of the Late Devonian period, and a full 172 million years after the Cambrian explosion saw the rapid diversification and speciation of some the earliest complex eukaryote life. The first forests were in the process of transforming the landscape of the supercontinent Gondwana, unconstrained by the lack of large herbivorous animals, and the first tetrapods were appearing in the fossil record. Who knows what transformations the world and life will undergo during the next 370 million years?

I should note that the error bars for these numbers are high, and I’m making no concrete predictions here for the inhabitants of the world 369 million years from now to call me out on. The habitable zone as a theory itself is fraught with assumptions that are, at this stage of understanding, regrettably necessary and regularly challenged and amended.

The Clock is Ticking

Like as the waves make towards the pebbl’d shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end

-William Shakespeare, Sonnet LX

It remains intrinsically unsettling to consider the fact that at some point our lovely blue-green home planet will eventually lose its ability to support life. It is certain that, whether after 4.91 billion years or not, the edge of the gradually advancing theoretical boundary of habitability will near planet Earth; now an apocalyptic world of blistering heat and desolation, unrecognisable from today’s lush, watery paradise. As Sol’s mass, radiative output and surface temperature steadily increase, the Earth’s climate will eventually become scorching. The fundamental biogeochemical mechanisms that help to regulate the Earth’s climate will break down, buckling under the strain of the ever encroaching Sun, and a ‘runaway greenhouse‘ crisis will result. Caused by the evaporation of the oceans and the initiation of a irreversible water vapour/temperature feedback mechanism, the runaway greenhouse is thought to be responsible for the of climate of Venus today. High temperatures result in more water vapour in the air and higher humidity, which in turns boosts the temperature further causing more evaporation and more humidity. Eventually the Earth will become enveloped in thick, impenetrable cloud, insulating the surface and acting like an planet-wide pressure cooker, undoubtedly heralding the end of life on the Earth as we know it.

As the Sun grows larger and hotter, high energy particles from the solar wind will eventually strip away this thick atmosphere which will be forever lost to space. The parched, molten husk of the Earth, former home to countless organisms and every human ever to exist, as well as the stage to every single event, from the minuscule to the revolutionary that took place for nearly 5 billion years, will probably be devoured by the Sun long after it has become inhospitable for life, an incomprehensibly distant 7 billion years from now.

What Earth may look like 5-7 billion years from now – after the Sun swells and becomes a Red Giant. (Wikipedia)

The Earth, my friends, is lost. But fear not, perhaps we could move out to Mars? Our dusty neighbour will move into the habitable zone approximately 1.7 billion years from now, and stay there for the remainder of the Sun’s main sequence lifetime. The Sun in it’s death throes will make for an incredible sight in the Martian sky. However, Mars has a very chaotic orbit, making it difficult to determine exactly where it will be in the distant future. On top of all this, it’s hard to predict what conditions will be like around the ageing Sun.

Well, so much for the Earth and Mars. Let’s hope that in the preceding 370 million years our descendants make it to a better world.

The Lives of Planets

The Super-Earth Gliese 581d (top left of plot) has an approximate habitable period of over 50 billion years. I don’t know about you, but I have real difficultly grasping the truly unfathomable immensity of that amount of time. Research suggests that its star, red dwarf Gliese 581, is approximately 8 billion years old, and therefore the habitable zone has been home to Gliese 581d for 1.4 times as long as the Earth has existed for, yet it is only 13% of the way through its total habitable period. Still, this isn’t to say that it’s ‘habitable’; there are plenty of other factors (its large mass for example) that suggests that it’s not a place where life would thrive. Although, given 50 billion years who knows what evolution could throw up?

Gliese 667Cc, also orbiting a red dwarf star, will be in the habitable zone for 1.8 billion years because it formed straddling the inner edge – it won’t be (relatively) long until the heat of its star overwhelms its ability to maintain a habitable environment, if it has one at all. It’s a similar story for the Super-Earth HD 85512 b. Despite it’s location in the habitable zone, it’s still too close to be habitable for any considerable length of time – a mere 603 million years which, if we draw on Earth’s evolutionary history for comparison, is barely enough time for the denizens of the Cambrian to make themselves comfortable, if we extrapolate backwards (and ignore the ~3.5 billion years that it took to get to this stage in the first place).

Kepler 22b is another excellent candidate for a habitable planet, orbiting well within the habitable zone and remaining there for 3.4 billion years. On Earth, 3.4 billion years ago, it is thought that the first primitive organisms had emerged and were building reefs (stromatolites) and going about their daily business of dividing and multiplying – the kind of stuff that modern bacteria tend to fill their lives with. From these humble beginnings we emerged eons later; perhaps the same can be true on Kepler 22b?

In the End…

I realise this has been quite a long article, and I appreciate you sticking it out to the end. I hope that you found it as interesting to read as I did to write. The concept of habitability through time hasn’t been explored in great detail, and I hope to refine these numbers and tweak the model and its assumptions to improve the accuracy of the estimates in the future. Nevertheless, I found it an interesting, and rather humbling, thought experiment if nothing else.

Perspective is important, and yet always in short supply. We’re currently 92% of the way through our planet’s habitable period, enjoying the twilight years of its habitable lifetime. We have to remember that the Earth isn’t going to be able to shelter us indefinitely and that all planets’ lives come to an end at some point. It’s worth bearing that mind when considering that despite our delusions of grandeur, our brief residence on this planet has been a fleeting blip in its long and tumultuous history. Our future may well be too.

![eso0939a[1]](https://i0.wp.com/1.bp.blogspot.com/-fCbj9eEyNOs/USEV0o5fS2I/AAAAAAAAAuA/-nmSLVjPrvU/s1600/eso0939a.jpg)