There were two kinds of landscape characteristic of the inner planets of the Sun: the purposeful and the desolate.

Stanislaw Lem – Fiasco (1986) [Ch.1, tr. Michael Kandel]

A loose rock tumbles slowly down a slope in a lonely valley on Mars. The hill of its origin seems unfamiliar and alien – it is more crimson and notably steeper than any rise on Earth due to Mars’ oxidizing environment and lower gravity. A loose conglomerate of ruddy scree, it seems completely devoid of life. The rock, idle in its elevated resting place for perhaps eons, now dislodged by a chance landslide caused by a violent Martian windstorm, rolls to a stop in a new location in the dry valley below. No human eyes have ever seen this boulder, no one has sat atop it to survey the panorama of the valley where it sat, or pounded it with a rock hammer to determine its composition, or crudely scrawled their initials into its surface in an attempt to immortalize a teenage love affair. What purpose, if any, does this boulder serve? Life cannot shelter beneath it or break it down for nutrients because no life exists on this frigid, desiccated planet. It inhabits an exclusively abiotic world, and whilst it will be shaped by powerful winds into exotic and unfamiliar forms, it will eventually be blown to dust by the continual onslaught of sandstorms, dissipating gradually, grain by grain, into the chaotic atmosphere. The universe seems no richer for its passing.

An alien world? Actually, this is the Atacama Desert in Chile, possibly the world’s oldest desert and one of the driest places on the planet. (via i09.com/Benjamin Dumas)

Desolation is a ubiquitous feature of the solar system. From the barren, scorched and pockmarked surface of Mercury, to the icy solitude of the gas giants, and out to the lonely minor planet Pluto in its long, dark trundle around the Sun, these are entire worlds devoid of life and the patient sculpting of natural process we are so familiar with on Earth. Their terrain is of great interest scientifically, but it is obvious that these are worlds very different to our own. They lack a certain something, an inherent dynamism that it seems only biology can imbue. They seem alien, and they are in some sense, but this feeling of other-worldliness issues forth from the unfamiliar landforms and empty horizons, broken here and there by topographies of pure abiological physicality. Nothing about these geographies serves a ‘purpose’. The craters of Mercury, or Mars, or any of the moons of Jupiter or Saturn, stand magnificent in their grandeur, but alone in the emptiness of space: many will never be explored, never investigated, chaotic in their form and distribution, but ultimately meaningless in their existence. It is my expectation that if we were to find another planet on which life had a foothold, that world would seem somehow more familiar to us, if undoubtedly exotic and bizarre, than a planet entirely devoid of biology.

This lack of purpose, of meaning, is obviously an inherently human concept, and whilst it results in an obvious planetary dichotomy (as illustrated by the quote above), it is this contrast that should provide us with perspective on our own planet and a greater appreciation for even the smallest action borne from the ancient, intimate dance between life and our world, choreographed by natural selection and honed by a run lasting billions of years. For if we consider these alien features to be meaningless and purposeless, it follows that the only ‘purpose’ that exists is that which began on Earth, and which emanates now ever outwards, shaping, and in some cases, biasing, our view of these barren worlds. Meaning is a concept that we as humans can and do impose upon desolate landscapes. We name features on distant planets, we photograph their lonely surfaces and seek explanations for their existence, but only as an aside in our quest for a greater understanding of our place and purpose. Even here on Earth we occupy the least biologically productive environments, sometimes for science, or for economic gain, or just for the challenge, but by our very presence in these once vacant landscapes, we provide a center of purpose. The once empty environment now provides a backdrop to the human drama, an extension of the boundless stage on which we carry out the acts of our lives; a silent witness to hours, days or years of collective human strife and trivialities. But is this really all meaning is? An inherently dichotomous characteristic of place that only exists relative to biology’s insight or attention?

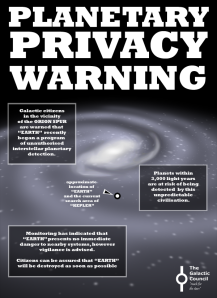

In searching for a word to convey this sense of emptiness, of this abiotic ‘nothingness’, the limitations of terrestrial linguistics shaped by our Earth-bound experiences and history are revealed, and the true magnitude of the desolation – often global, near complete – remains difficult to comprehend and to express cogently. A world without any ‘meaning’, any direction, any sense of teleological drive. An environment surrendered to entropy and shaped by chaos and the haphazard actions of an abiotic ‘nature’. This is a nature unbounded by the necessities of life, in which soils and rocks remain untouched by biology but are instead molded, as clay in the hands of an inanimate potter, by purely physical processes: wind, fluids, irradiation and planetary tectonism. It seems that these are the environments most favored by the universe as they litter our solar system, and almost certainly exist around billions of other stars in our galaxy and beyond. Can it really be that an entire galaxy could exist in this state of meaningless stasis? Barren, empty reaches awaiting the arrival of life to imbue meaning upon the void?

It is possible that humans are the only intelligent observer species ever to have arisen in this galaxy. If that is the case, we have a great responsibility, not only to preserve our planetary sanctum for future generations and to continue to unravel the esotericisms of the universe, but to further safeguard our existence as the fount, the point source, of absolute meaning. The universe, it seems, is indifferent to our struggles, but we can elevate ourselves above the insignificant by our individual introspection and collective scientific extrospection.

We are the Gods of Purpose, and all the universe is our Eden.